The Lazarus Trial and a Case for Changing the Laws Around Consent

You probably heard that Luke Lazarus was found not guilty of sexual assault this week. What you might not have heard is that he was found not guilty despite a jury and two judges determining that the complainant, Saxon Mullins, had NOT consented to sex with him. Upon finding that piece of information out, most people are confused.

If someone doesn’t consent, isn’t that rape?

Well, the answer to that question might depend on where you live.

Saxon Mullins’ identity has been protected for five years because she is a sexual assault complainant. Five years ago, Saxon Mullins was eighteen and had the first sexual encounter in her life. I don’t want to detail that encounter here. It’s Mullins’ story. If you aren’t familiar with this case, here are Mullins’ own words, but if you can’t read them, for brevity I will point out that the sex happened within four minutes of the pair meeting and it was anal.

Mullins calls the encounter rape.

Lazarus states it was a misunderstanding.

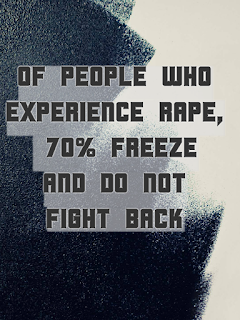

Lazarus’ defence to the allegations was generally that Mullins followed directives during the encounter and did not leave, and this was enough to convince him she was consenting. Mullins has explained her actions as being alone with a stranger she just met, and being scared. She said she went into autopilot.

This is something many rape survivors recognise: shutting down/freezing.

During his first trial in 2015, Lazarus was found guilty by a judge and jury. He served 11 months in prison. His legal team appealed the court and due to media saturation, he was granted a retrial alone with Judge Robyn Tupman. While Judge Tupman agreed with the previous judge and jury that Mullins didn’t consent, it was not clear - beyond reasonable doubt - that Lazarus knew she didn’t consent.

In Judge Tupman’s judgement, she said: “Whether or not she consented is but one matter. Whether or not the accused knew that she was not consenting is another.”

Judge Tupman decided the prosecution in the 2015 trial didn’t prove that Lazarus didn’t have reasonable grounds for believing Saxon consented. This was because Mullins had lacked resistance. Judge Tupman also referred to “contemporary morality”. What this seems to relate to is that Lazarus had friends testify, that they had anal sex on first dates, therefore it might not be unreasonable for Lazarus to believe a virgin 18-year-old would want to have anal sex within literally four minutes of meeting someone. (note: this is my understanding of it and I am a layperson, not versed in legalese).

The general idea of Tupman’s judgement was that Mullins didn’t consent, but because Mullins did not physically resist, there is doubt that Lazarus truly knew she was not consenting.

So, how did this situation come about? How did Saxon Mullins’ justice get stuck in a grey area?

Crown prosecutors are the public prosecutors in our legal system, but Australia’s states don’t have common consent laws. In NSW, when someone is on trial for sexual assault, the crown has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the complainant did not consent.

Anthony Whealy QC, a former Justice of the Supreme Court of NSW, explained what effect this phrasing has within trials:

“(this creates) the unfortunate consequence of focusing almost exclusively on the complainant ... and so the trials tend to excoriate the complainant, unfairly in many cases, and when you have a jury there, they can’t help but be affected by that sort of cross examination which can be very powerful and very damaging (to the complainant).

…(in trials, the crown must also prove)… that the defendant knew that consent was not given or was reckless as to whether consent was given. Or if he had a belief that consent was given, that it has to be on reasonable grounds.”

Other states and territories have different wording in laws in regards to what consent is. The best practice example is said to be either Tasmania or Victoria, wherein (according to Anthony Whealy):

“the crown must prove that the complainant gave free agreement to sexual intercourse taking place ... and the judge is asked to direct the jury that if the complaint said or did nothing at the time of the sexual intercourse, that means she did not give her free agreement.”

This is an important difference. This wording change means that instead of trying to prove that complainant did not consent, the crown must prove the complainant gave free agreement. This switches the focus from the complainant to the accused. In this case, instead of focusing on the ways the complainant didn’t consent (i.e. when did Mullins say no, why didn’t Mullins leave, why did Mullins follow directives) the trial can focus on the ways the accused thought they had free agreement to the sexual intercourse taking place. The burden of proof, in a way, shifts from complainant to accused.

Mullins has endured two trials and two appeals. She has endured where so many women would have given up or never even started. And we should recognise her bravery, in taking this to court in the first place (many women wouldn’t) and enduring the trial and now, sacrificing her anonymity to talk to Four Corners about her ordeal.

Because Mullins has continued to push for justice, and talked to Four Corners, NSW Attorney General Mark Speakman has questioned if the law in NSW is adequate.

“What this shows is that there’s a real question about whether our law in New South Wales is clear enough, is certain enough, is fair enough. That's why I’ve asked the Law Reform Commission to look at the whole question of consent in sexual assault trials.”

NSW Minister for the Prevention of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Pru Goward says: “The key message the investigation drove home was the need to explicitly ask for permission to have sex … If it’s not an enthusiastic ‘yes’, then it’s a ‘no’.”

Changing the laws brings the need to discuss enthusiastic consent, what it looks like and how to obtain it. Enthusiastic consent not only offers greater protection for, especially, women, it also offers a new world for women where the bar for our sexual encounters is not as low as “well she didn’t move away from me, so I assume she wanted it”.

Our laws seek to enshrine what we believe as a society. Ensuring sexual encounters begin as an enthusiastic yes is a starting point that shifts all parties to actively pleasure seeking people, instead of one aggressor and a motionless body. It removes assumption. It forces us to be clear and to seek input from our sexual partners about what they do and do not want. It forces us to need interest, and excitement from both partners.

If Lazarus had been tried under the Tasmania/Victoria laws, would he be guilty? We can’t say. But if we can review our laws and bring them in line with best practice, maybe we’ll see for the sexual assault trials in future.

This review may be a way to move our laws surrounding consent, and our justice, out of the grey area.

By: Tee Linden

If someone doesn’t consent, isn’t that rape?

Well, the answer to that question might depend on where you live.

Saxon Mullins’ identity has been protected for five years because she is a sexual assault complainant. Five years ago, Saxon Mullins was eighteen and had the first sexual encounter in her life. I don’t want to detail that encounter here. It’s Mullins’ story. If you aren’t familiar with this case, here are Mullins’ own words, but if you can’t read them, for brevity I will point out that the sex happened within four minutes of the pair meeting and it was anal.

Mullins calls the encounter rape.

Lazarus states it was a misunderstanding.

Lazarus’ defence to the allegations was generally that Mullins followed directives during the encounter and did not leave, and this was enough to convince him she was consenting. Mullins has explained her actions as being alone with a stranger she just met, and being scared. She said she went into autopilot.

This is something many rape survivors recognise: shutting down/freezing.

|

| Stat according to victimfocus.org.uk |

During his first trial in 2015, Lazarus was found guilty by a judge and jury. He served 11 months in prison. His legal team appealed the court and due to media saturation, he was granted a retrial alone with Judge Robyn Tupman. While Judge Tupman agreed with the previous judge and jury that Mullins didn’t consent, it was not clear - beyond reasonable doubt - that Lazarus knew she didn’t consent.

In Judge Tupman’s judgement, she said: “Whether or not she consented is but one matter. Whether or not the accused knew that she was not consenting is another.”

Judge Tupman decided the prosecution in the 2015 trial didn’t prove that Lazarus didn’t have reasonable grounds for believing Saxon consented. This was because Mullins had lacked resistance. Judge Tupman also referred to “contemporary morality”. What this seems to relate to is that Lazarus had friends testify, that they had anal sex on first dates, therefore it might not be unreasonable for Lazarus to believe a virgin 18-year-old would want to have anal sex within literally four minutes of meeting someone. (note: this is my understanding of it and I am a layperson, not versed in legalese).

The general idea of Tupman’s judgement was that Mullins didn’t consent, but because Mullins did not physically resist, there is doubt that Lazarus truly knew she was not consenting.

So, how did this situation come about? How did Saxon Mullins’ justice get stuck in a grey area?

Crown prosecutors are the public prosecutors in our legal system, but Australia’s states don’t have common consent laws. In NSW, when someone is on trial for sexual assault, the crown has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the complainant did not consent.

Anthony Whealy QC, a former Justice of the Supreme Court of NSW, explained what effect this phrasing has within trials:

“(this creates) the unfortunate consequence of focusing almost exclusively on the complainant ... and so the trials tend to excoriate the complainant, unfairly in many cases, and when you have a jury there, they can’t help but be affected by that sort of cross examination which can be very powerful and very damaging (to the complainant).

…(in trials, the crown must also prove)… that the defendant knew that consent was not given or was reckless as to whether consent was given. Or if he had a belief that consent was given, that it has to be on reasonable grounds.”

Other states and territories have different wording in laws in regards to what consent is. The best practice example is said to be either Tasmania or Victoria, wherein (according to Anthony Whealy):

“the crown must prove that the complainant gave free agreement to sexual intercourse taking place ... and the judge is asked to direct the jury that if the complaint said or did nothing at the time of the sexual intercourse, that means she did not give her free agreement.”

This is an important difference. This wording change means that instead of trying to prove that complainant did not consent, the crown must prove the complainant gave free agreement. This switches the focus from the complainant to the accused. In this case, instead of focusing on the ways the complainant didn’t consent (i.e. when did Mullins say no, why didn’t Mullins leave, why did Mullins follow directives) the trial can focus on the ways the accused thought they had free agreement to the sexual intercourse taking place. The burden of proof, in a way, shifts from complainant to accused.

Mullins has endured two trials and two appeals. She has endured where so many women would have given up or never even started. And we should recognise her bravery, in taking this to court in the first place (many women wouldn’t) and enduring the trial and now, sacrificing her anonymity to talk to Four Corners about her ordeal.

Because Mullins has continued to push for justice, and talked to Four Corners, NSW Attorney General Mark Speakman has questioned if the law in NSW is adequate.

“What this shows is that there’s a real question about whether our law in New South Wales is clear enough, is certain enough, is fair enough. That's why I’ve asked the Law Reform Commission to look at the whole question of consent in sexual assault trials.”

NSW Minister for the Prevention of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Pru Goward says: “The key message the investigation drove home was the need to explicitly ask for permission to have sex … If it’s not an enthusiastic ‘yes’, then it’s a ‘no’.”

Changing the laws brings the need to discuss enthusiastic consent, what it looks like and how to obtain it. Enthusiastic consent not only offers greater protection for, especially, women, it also offers a new world for women where the bar for our sexual encounters is not as low as “well she didn’t move away from me, so I assume she wanted it”.

Our laws seek to enshrine what we believe as a society. Ensuring sexual encounters begin as an enthusiastic yes is a starting point that shifts all parties to actively pleasure seeking people, instead of one aggressor and a motionless body. It removes assumption. It forces us to be clear and to seek input from our sexual partners about what they do and do not want. It forces us to need interest, and excitement from both partners.

If Lazarus had been tried under the Tasmania/Victoria laws, would he be guilty? We can’t say. But if we can review our laws and bring them in line with best practice, maybe we’ll see for the sexual assault trials in future.

This review may be a way to move our laws surrounding consent, and our justice, out of the grey area.

By: Tee Linden

Thanks for the informative blog.Sydney Criminal Lawyers George Sten & Co is a criminal law firm based in the central business district of Sydney, Australia.

ReplyDeleteSydney Criminal Law Firm