2017, time’s up.

To many, 2017 will be remembered as a very bad year. To me, 2017 will be remembered as the year women got together to start a series of revolutions against structural inequality. 2017 was the year of women’s anger.

2017 was the year of the Women’s March on Jan 21st, a worldwide protest led by women. It was in reaction to Trump’s inauguration, but the goal was to protect hard-won rights, to safety, to health, to the right of existence for diverse communities. That goal echoed around the world, including here in Sydney, pinked and pussy-hatted women gathered around the world, together.

2017 was also the year of the #metoo silence breakers. Post Weinstein, the long-silenced discussions of sexual harassment began to have a space, and women and men started sharing stories of sexual harassment and assault. There were questions thrown up about the movement, challenging power structures always brings questions, but there are more people within the movement still pushing back.

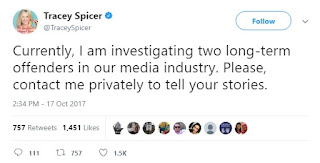

#Metoo is an important movement in America, and its important movement here, around the world, spreading like a grassfire. In the Spanish-speaking world, they have #YoTambien. The Italians have #QuellaVoltaChe “that time when”. The French have #BalanceTonPorc – “snitch out/expose your pig” (my personal favourite). Wherever it is, this movement brings the discussion of sexual assault and harassment to the mainstream. And while here in Australia, some men are being named by women, Don Burke and Craig Mclachlan among them, (Tracey Spicer taking names, literally)

there’s still a long way to go for us in 2018.

In 2017, as feminism became an everyday word

(feminism was Merriam-Webster’s word of the year in 2017 and was the most

searched for word), feminists are becoming more aware that feminism doesn’t

look the same to everyone. What I mean is, we’re becoming more aware of

intersectionality: anecdotally, I hear that word "intersectional"

more in discussions, and in action, I saw it in the calling out of the #metoo

hashtag, amplified by (and at first credited to) Alyssa Milano. The creator of

the movement was Tarana Burke, and she was included in Time’s silence breakers.

This is a good example, but obviously, there’s more work to do in this space.

Julia Baird, with Hayley Gleeson, did a series of stunning exposes into the tangle of domestic abuse and religion. Some of the links here, here and here.

This is a good example, but obviously, there’s more work to do in this space.

Julia Baird, with Hayley Gleeson, did a series of stunning exposes into the tangle of domestic abuse and religion. Some of the links here, here and here.

This amazing investigation was bolstered by the

explosive #churchtoo

created by Hannah Paasch and Emily Joy. As Hannah from America states:

The more women speak out, the harder men find

it to block their ears. But men have had a lot of practice at blocking their

ears — it is part and parcel of male privilege… Even in churches that don't

teach headship and submission, male privilege is present."

Because of the ABC investigation or the

#churchtoo movement – or maybe a little of both – we saw a flood of apologies

come through from Australia’s religious institutions. The Sydney Anglican

church confessed to domestic abuse in its ranks and introduced new policy aimed

at weeding out offenders from its ranks.

There was also an apology from the Baptist

church and the creation of SAFER a

tool to “help churches understand, identify and respond to domestic and family

violence”.

And of course, we achieved a measure of

equality in regards to marriage. Australia’s postal survey was a dangerous,

cowardly farce that shoved many Australians into harm’s way. But despite that,

marriage equality was passed. This isn’t just a win for feminists of course,

but feminists believe in equality – for all. Magda Szubanski’s

tireless efforts

to reach out to Australians of all stripes , and Penny Wong’s moving, determined

speeches in

Parliament where she, as an openly gay member, is outnumbered, definitely

contributed to the win.

#Timesup is an American campaign to steal out discrimination in workplaces, backed by a woman-powered legal defence fund. It’s already making beautiful, black-clad celebrity waves.

Australians need to follow the momentum of this movement, and not just in the entertainment industry. We need to make it easier for people to report.

As the Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins has said: “Research has shown that gender inequality and community attitudes about women and their role in society contribute significantly to sexual harassment and other forms of sexual violence against women.

“Gender

inequality is the result of the unequal power distribution between men and

women, and is reinforced by gender discrimination and structures that perpetuate

inequality.”

(Link: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/news/stories/reason-be-hopeful-about-changes-attitudes-sexual-harassment)And as Liberty Sanger, chair of the Equal Workplaces Advisory Council Victoria, points out, people only have six month time limit for making harassment or discrimination complaints to the Australian Human Rights Commission. (Link to complaint form: http://www.humanrights.gov.au/complaints/make-complaint/complaint-form) perhaps, with what we know about all the personal and professional roadblocks to reporting harassment, six months is not a long enough period.

There are things we can improve on in 2018. And there are movements already rolling in January (including the anniversary of the Woman’s March that took place on 21st January at Hyde Park)

The message of the movements is clear:

“No more silence. No more waiting. No more tolerance for discrimination, harassment or abuse.

Times up.” (from the Times up website)

By Ted Eytan from Washington, DC, USA [CC

BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia

Commons

Article by Tee Linden

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete